Everything You Need

From book covers to social media posts to full outlines and in-depth chapters, everything you need to bring your book idea to life.

See below for real examples from "Portable Harvests" - a complete book created with One Great Book. Read actual chapters, explore the full outline, and see the professional covers and marketing materials you'll receive.

Interactive Publishing Console

Your complete marketing arsenal - ready to copy and deploy. Everything from social posts to book descriptions, optimized and waiting for you.

Click each section below to see actual content generated with One Great Book.

What you get:

Everything to publish and promote your book: Kindle Direct Publishing-ready manuscript, 3 professional covers, back cover copy, and social media posts for all major platforms.

Example Book

Portable Harvests: The Renter's Guide to Growing Food Anywhere

by Anne Bennett

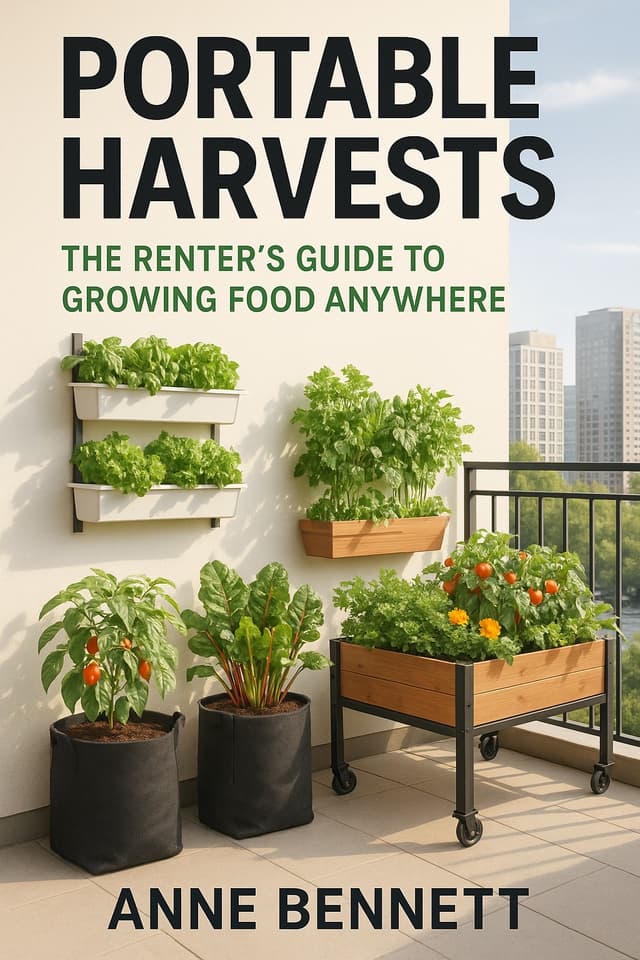

Professional Book Covers

AI-generated designs ready for print and digital publishing

Back Cover Copy

Compelling marketing description optimized to sell your book

Think growing your own food is impossible as a renter? With over 44 million American households renting—and most traditional gardening advice tailored for homeowners—it's easy to feel excluded or overwhelmed by landlord rules, tiny balconies, or frequent moves. But what if your rental constraints are actually the secret to a thriving, innovative food garden? Drawing on a decade across eight rentals, and thousands of pounds of food harvested in containers, I transform the renter's dilemma into a powerful advantage. My systematic, data-backed approach—tested by over 3,000 members in my online community—proves that portability and creativity, not acreage, are the keys to sustainable homegrown harvests. **This book equips you to:** - Reframe every move as a chance to upgrade your garden, not start over - Uncover productive microclimates in even the most unlikely spaces - Select the right crops and containers for results—not regret - Sidestep the expensive mistakes that derail most new gardener-renters - Apply proven strategies for negotiating with landlords and maximizing yields Inside, you'll discover a practical, step-by-step framework that starts with a one-week assessment and builds toward modular, vehicle-ready garden systems—so you can grow meaningful food wherever life takes you, no matter your space or experience level. As founder of the largest online community for renter-gardeners, I bring twelve years of firsthand expertise—plus case studies from Phoenix to Minneapolis—to this essential guide. My work has empowered thousands to cultivate abundance in the most temporary of spaces.

Social Media Marketing Kit

Platform-optimized content for maximum engagement

Still think renters can't grow real food? Rental restrictions might actually be hiding your *biggest* creative advantage. If you had to move tomorrow, could your garden come with you? #portablegardening

Tried gardening in pots, ended up with a wilted mess? The truth: container size matters way more than you think. A 4-inch herb pot = almost guaranteed failure. Have you ever tried a 2-gallon upgrade?

Most advice ignores this: every move is a chance to *upgrade* your garden, not start over. How could your next move boost your harvest, not hurt it? (Portable Harvests digs into the step-by-step—ask me how!)

Trending hashtags included:

#PortableGardening #RenterGardening #ContainerGardening #ApartmentGardening #UrbanGardening #SmallSpaceGardening #BalconyGarden #RentalLife #HomegrownFood #FreshHerbs #GrowYourOwn #SustainableLiving #Permaculture #GardeningTips #PlantLife

📄 Complete Manuscript

Professionally formatted Word document

Portable Harvests: The Renter's Guide to Growing Food Anywhere

Word Document • 30,000-40,000 words • 15 chapters

Ready for Kindle Direct Publishing • Upload and sell immediately

🎉 Publishing Package Complete!

Everything you need to launch your book successfully is ready

What you get:

AI builds your complete book structure from your answers - detailed chapter outlines with summaries and key teaching points that guide your entire manuscript.

Portable Harvests

The Renter's Guide to Growing Food Anywhere

Chapter 1: Breaking the Myth: Why Renters CAN Grow Food Anywhere

This opening chapter debunks the widespread belief that gardening is only for homeowners. Readers will discover the unique opportunities and challenges of growing food as a renter, hear stories from real renters who've succeeded, and learn why portable food gardening is not only possible but often more creative and rewarding.

Key Points:

Chapter 2: Renter Realities: Understanding Your Space and Situation

Readers will assess their specific rental context—apartment, townhouse, or house with a tiny yard—and learn how to evaluate their gardening potential. This chapter covers foundational container gardening principles (soil, light, water) and introduces the 'vehicle test' for true portability.

Key Points:

Chapter 3: Designing Your Portable Garden: Systems That Move With You

This chapter introduces the core philosophy and practicalities of portable garden design. Readers will learn how to select truly moveable containers, standardize sizes for easy transport, and plan their garden around vehicle capacity.

Key Points:

Chapter 4: Avoiding Renter Gardening Pitfalls: What NOT to Do

Drawing from personal experience and hundreds of community stories, this chapter highlights the most common mistakes renters make when starting portable gardens—and how to avoid them. Readers will learn how to start small, choose the right containers, and plan for portability from day one.

Key Points:

Chapter 5: Container Gardening Essentials: Soil, Water, Light, and Beyond

This foundational chapter dives deeper into the specifics of container gardening—choosing the right soil mix, watering strategies for pots, maximizing light in challenging spaces, and troubleshooting common problems.

Key Points:

Chapter 6: Negotiating With Landlords: Scripts, Proposals, and Winning Permission

Landlord approval is often the biggest barrier for renters. This chapter equips readers with proven negotiation strategies, scripts, and proposal templates. Learn how to present your garden as an asset—not a liability—using visual aids and written agreements.

Key Points:

Chapter 7: Adapting Permaculture Principles for Small, Temporary Spaces

Permaculture isn't just for landowners! This chapter shows how renters can creatively apply permaculture thinking—like stacking functions, catching/storing energy, polyculture planting, and succession cropping—in tiny or temporary spaces.

Key Points:

Chapter 8: Microclimates and Maximizing Space: Growing More in Less Room

This chapter teaches readers to observe and harness microclimates—making the most of sun, shade, wind, and heat in their unique rental environment. Learn vertical gardening techniques, creative use of odd corners, and how to select crops for challenging conditions.

Key Points:

Chapter 9: "Confidence Crops": Selecting Reliable Varieties for Renters

Not all crops are created equal—especially for renters! This chapter provides detailed recommendations for herbs, vegetables, and fruit varieties that thrive in containers and transient situations. Readers will learn which crops offer fast rewards ('confidence crops').

Key Points:

Chapter 10: "Workhorse" Tools and Templates: Setting Yourself Up for Success

This hands-on chapter introduces readers to the most-used tools—setup checklists, seasonal calendars, troubleshooting guides, soil calculators, inventory sheets, and more. Each tool is explained with practical examples so readers can immediately put them into action.

Key Points:

Chapter 11: "The Vehicle Test": Planning Gardens That Survive Every Move

Moving is inevitable for renters—but losing your garden doesn't have to be. This chapter teaches readers how to design with mobility in mind from day one. Learn how to standardize containers, label plants for easy packing, and develop a personalized moving plan.

Key Points:

Chapter 12: "Version 2.0": Redesigning After Each Move (and Loving It)

"Losing" a garden becomes an opportunity with the right mindset. This chapter reframes moving as a chance to upgrade—helping readers assess what worked at their last place, adapt to new conditions quickly, and see each move as a creative evolution.

Key Points:

Chapter 13: "Renter Spotlights": Community Wisdom and Cautionary Tales

"You're not alone!" This chapter features diverse stories from the online community—spotlighting creative solutions to tough situations, cautionary tales about what went wrong, and inspiring examples of renters building thriving gardens against the odds.

Key Points:

Chapter 14: "Portable Harvests Forever": Becoming Your Own Garden Mentor

This final chapter empowers readers not just to grow food anywhere themselves—but to become mentors in their own communities. Readers will reflect on their journey from beginner to confident mobile gardener and celebrate that they now 'own' their food supply—no matter where they live.

Key Points:

What you get:

AI writes your complete manuscript from your answers and outlines - up to 15 professionally-written chapters (30,000-40,000 words total). Each chapter is structured, engaging, and written in your book's unique voice.

See for yourself: Below are the first 3 chapters from a real book created with One Great Book.

Chapter 1: Breaking the Myth: Why Renters CAN Grow Food Anywhere

1,879 words

I was 22 years old, standing in the produce section of a Portland grocery store, staring at a $4 package of wilted basil that would last maybe three days in my fridge. I'd just signed the lease on my first rental—a tiny apartment with a north-facing balcony that got about as much sun as a cave. The landlord had made it crystal clear during the walkthrough: "No changes to the property. No holes in walls. No garden beds."

But here's the thing that hit me as I held that overpriced basil: nowhere in that conversation had anyone said I couldn't grow my own food.

That moment sparked a 12-year journey across eight different rentals, where I've learned something that most people—including most gardening books—get completely wrong. The myth that you need to own land to grow meaningful amounts of food isn't just false. It's holding back millions of renters from one of the most rewarding, practical skills they could develop.

If you've ever felt like gardening was something "other people" do—people with houses and yards and permanent addresses—this book is going to change your mind. Not just about gardening, but about what's possible when you're living a mobile life.

The Great Gardening Myth

Walk into any bookstore's gardening section and you'll see what I mean. Book after book assumes you own your space. They talk about "improving your soil" (what soil?), "planning your landscape" (my landscape is a concrete balcony), and "long-term garden investments" (I might move next year). The entire gardening industry seems designed for people who've put down roots—literally and figuratively.

This creates a massive blind spot. According to recent data, over one-third of American households rent their homes. That's roughly 44 million households who've been essentially told that growing their own food isn't for them. We're supposed to accept that we'll forever be dependent on grocery stores, farmers markets, and whatever produce happens to be available and affordable.

But what if that entire premise is wrong?

What if renting doesn't disqualify you from growing food—it just means you need different strategies?

What if the constraints of rental living actually force you to become a better, more creative gardener?

I've spent over a decade proving these questions have surprising answers. Across eight rentals—from studio apartments to houses with postage-stamp yards—I've grown thousands of pounds of food in containers that moved with me. I've negotiated with landlords who initially said "absolutely not" and watched them become my biggest garden advocates. I've helped over 3,000 renters in my Facebook group do the same thing.

The myth that renters can't garden isn't just wrong—it's backwards. Some of the most innovative, productive, and resilient food gardens I've seen belong to renters.

Why Renters Actually Have Advantages

Here's what the homeowner-focused gardening world doesn't want to admit: renting comes with some serious advantages for food growing.

First, you're forced to think modularly from day one. When you know you might move, you can't just throw plants in the ground and hope for the best. You have to design systems that work, that produce quickly, and that can adapt to new conditions. This constraint makes you a more intentional gardener.

Second, you get to experiment without permanent consequences. That expensive fruit tree that might take five years to produce? Not a great investment when you rent. But that means you focus on crops that give you results in weeks or months—herbs, salad greens, cherry tomatoes, peppers. You learn what actually feeds you, not what looks impressive.

Third, every move is an opportunity to upgrade. When I lived in that cave-like apartment in Portland, I learned everything about shade gardening. When I moved to a sunny patio in Denver, I could apply those lessons while exploring sun-loving crops I'd never grown before. Each rental teaches you something new about microclimates, plant selection, and creative problem-solving.

Fourth, you develop genuine portability skills. Homeowners might talk about "sustainable gardening," but renters actually practice it. When you have to pack up your entire garden and move it 500 miles, you quickly learn what's truly essential and what's just garden center marketing.

Most importantly, you learn to see opportunities where others see limitations. That narrow strip along your apartment building's fence? Perfect for vertical gutter gardens. That hot concrete patio your landlord apologized for? Ideal microclimate for heat-loving peppers and herbs. The "terrible" north-facing balcony? Actually great for lettuce and leafy greens that bolt in full sun.

Real Renters, Real Results

Let me tell you about Maria, a member of my Facebook group who gardens on a third-floor apartment balcony in Phoenix. When she first posted, she was convinced the Arizona heat made container gardening impossible. "Everything just fries," she wrote.

But Maria didn't give up. She started observing her space differently. She noticed that her balcony got brutal afternoon sun but stayed relatively cool in the mornings. She figured out a shade cloth system using shower curtain rings that she could adjust throughout the day. She focused on heat-tolerant crops and learned to water twice daily during summer.

Two years later, Maria grows about 40% of her vegetables on that balcony. She's got a rotation system that keeps her in fresh salads year-round, and her herb production has completely eliminated her grocery store herb budget. More importantly, she's become the go-to person in our group for desert container gardening advice.

Then there's James, who was renting a house with a beautiful front yard that he wasn't allowed to touch. Instead of seeing this as a limitation, he approached his landlord with a proposal: he'd maintain the existing landscaping for free in exchange for permission to add some containers along the side of the house. The landlord loved the idea of free yard maintenance, and James ended up with more growing space than he'd originally hoped for.

Or consider Sarah, who lives in Minneapolis and was convinced that container gardening couldn't work in harsh winters. She started with a few herbs on her kitchen windowsill, then expanded to cold-hardy greens in containers she could move into her unheated garage during the worst weather. Now she's growing food year-round and has inspired three neighbors to start their own container gardens.

These aren't exceptional people with special skills or unlimited budgets. They're renters who decided to challenge the assumption that their living situation disqualified them from growing food.

The Creativity Factor

Here's something I've observed over and over: constraints breed creativity. When you have unlimited space and resources, it's easy to be lazy with your garden design. You can spread plants out, use whatever containers catch your eye, and not worry too much about efficiency.

But when you're working with a 6x8 foot balcony and everything has to fit in your car when you move, every decision matters. You start thinking like a designer. How can this trellis serve multiple functions? Can these containers stack for storage? Which crops give me the most nutrition per square foot?

This forced creativity leads to innovations that benefit all gardeners. Some of the cleverest growing systems I've seen—vertical gutter gardens, stackable container systems, modular trellis designs—were invented by renters solving space and portability challenges.

The permaculture principle of "stacking functions" becomes second nature when space is limited. Your tomato trellis isn't just plant support—it's also a privacy screen, a windbreak, and a framework for shade cloth. Your containers aren't just planters—they're also seating when you put boards across them, and thermal mass to moderate temperature swings.

This kind of integrated thinking makes you a better gardener, period. It forces you to understand how different elements of your garden system interact, rather than just following a planting calendar.

Shifting Your Mindset

The biggest barrier to renter gardening isn't landlords or lack of space—it's mindset. Most renters have internalized the message that gardening requires permanence, ownership, and "proper" garden beds. They see their rental situation as temporary, so why invest in growing food?

But here's the reframe that changes everything: your garden isn't tied to your address. It's a skill set, a collection of systems, and a way of thinking that travels with you.

When I moved from Portland to Denver, I didn't lose my garden—I upgraded it. The containers came with me. The soil got refreshed and improved. The plants that couldn't make the journey became gifts for neighbors, and I started new ones from seeds I'd saved. My knowledge of what worked and what didn't became the foundation for an even better setup.

This is the "Version 2.0" mindset that transforms how you think about moving. Instead of seeing each move as starting over, you see it as an opportunity to apply everything you've learned to a new canvas. Your third rental garden will be better than your second, which was better than your first.

The goal isn't to create a permanent garden—it's to become a permanent gardener.

What This Book Will Teach You

Over the next thirteen chapters, I'm going to share everything I've learned about growing food as a renter. Not just the successes, but the failures that taught me what doesn't work. Not just my experience, but the collective wisdom of thousands of renters who've figured out creative solutions to challenges I've never faced.

You'll learn how to assess your rental space for growing potential, even if it seems hopeless at first glance. You'll discover which container systems are truly portable and which ones will leave you stranded on moving day. You'll get the exact scripts and strategies I use to get landlords excited about my garden plans instead of worried about property damage.

We'll dive deep into the practical stuff: soil mixes that work in containers, watering systems that don't require permanent installation, crop varieties that thrive in small spaces and produce quickly. You'll get checklists, templates, and troubleshooting guides based on real problems that real renters face.

But most importantly, you'll learn to see your rental situation not as a limitation, but as an opportunity to develop skills that most gardeners never master. You'll become someone who can grow food anywhere, adapt to any conditions, and take your garden with you wherever life leads.

Your Journey Starts Now

That 22-year-old standing in the grocery store holding overpriced basil had no idea what she was starting. She just knew she wanted fresh herbs and wasn't willing to accept that renting meant she couldn't have them.

Twelve years and eight rentals later, I've grown thousands of pounds of food in containers. I've eaten tomatoes I grew on apartment balconies, made pesto from basil that traveled with me across three states, and harvested salads from gutters mounted on rental property fences.

More importantly, I've learned that the question isn't whether renters can grow food—it's whether they're willing to think differently about how to do it.

If you're ready to challenge the myth that gardening requires land ownership, if you're tired of feeling excluded from the growing-your-own-food movement, if you want to develop skills that will serve you no matter where you live, then you're in the right place.

Your rental situation isn't holding you back from growing food. It's just requiring you to be more creative about how you do it.

And creativity, as you're about to discover, is where the real magic happens.

Chapter 2: Renter Realities: Understanding Your Space and Situation

2,384 words

Standing in my first rental apartment at 22, I thought I understood my limitations perfectly. North-facing balcony? Obviously terrible for plants. Concrete floor? Definitely not garden material. Landlord who'd already said "no changes"? Case closed.

I was wrong about almost everything.

What I didn't understand then—but learned through eight rentals and countless mistakes—is that every space has gardening potential. The trick isn't finding the perfect rental property. It's learning to see the opportunities that are already there, hidden in plain sight.

This chapter is about developing that vision. Before you buy a single container or negotiate with your landlord, you need to understand what you're working with. Not just the obvious stuff like how much space you have, but the subtle factors that determine whether your garden will thrive or struggle: light patterns, microclimates, water access, and yes, how everything will fit in your car when you move.

The Three Types of Rental Garden Spaces

After helping thousands of renters assess their spaces, I've noticed that most rental situations fall into three categories. Each comes with its own opportunities and challenges, and understanding which category you're in shapes everything from container selection to crop choices.

The Apartment Balcony or Patio

This is where most renters start, and honestly, it's often the most challenging space—but also the most rewarding once you crack the code. You're typically working with 20-100 square feet of concrete or decking, limited sun exposure, and weight restrictions you might not even know about.

The key insight about balconies is that they're microclimates within microclimates. That corner that stays shaded all morning might be perfect for lettuce that would bolt in full sun. The spot that gets blasted by afternoon heat could be ideal for peppers and herbs. The challenge is learning to read these patterns before you start planting.

I learned this the hard way at that first Portland apartment. I stuck tomato plants wherever I could fit containers, then wondered why the ones in the shadiest corner never produced fruit. It took me a full season to realize I was fighting my space instead of working with it.

Weight is the other major consideration with balconies. Most can handle way more than you'd expect—building codes typically require balconies to support at least 60 pounds per square foot. But wet soil is heavy, and you need to think about how weight is distributed. A dozen small containers spread across the space is usually better than one massive planter in the corner.

The Townhouse or Small House Patio

This is the sweet spot for many renters. You've got more space than an apartment balcony, often better sun exposure, and usually fewer weight restrictions. The challenge shifts from maximizing every square foot to designing a system that's still truly portable.

I lived in a Portland townhouse from 2019 to 2021 where the back patio was only 8x10 feet, but it felt luxurious compared to apartment balconies I'd worked with. The game-changer was being able to go vertical without worrying about wind load on a high-rise balcony. I could mount gutters on the fence, use taller trellises, and stack containers on plant stands.

The trap with patio spaces is thinking bigger automatically means better. I see renters get excited about having "real" space and immediately start planning elaborate setups with heavy planters and permanent structures. Remember: if you can't move it, you don't really own it as a renter.

The House with Tiny Yard Access

This category includes renters who have some ground space—maybe a small backyard, a side yard, or even just a strip along the driveway. The temptation here is to plant directly in the ground, but that's usually a mistake unless you're planning to stay for several years.

The advantage of yard access is flexibility. You can spread out, use larger containers, and take advantage of natural windbreaks and microclimates. The challenge is resisting the urge to go permanent. I've seen too many renters invest in raised beds they can't take with them, or plant perennials in the ground only to leave them behind.

James, one of my Facebook group members, found a clever middle ground. He was renting a house with a beautiful front yard he wasn't allowed to modify, but he negotiated with his landlord to maintain the existing landscaping in exchange for permission to add containers along the side of the house. He got more growing space than he'd hoped for, the landlord got free yard maintenance, and everything stayed portable.

Reading Your Space: The One-Week Assessment

Before you buy anything—and I mean anything—spend one week observing your space. This might feel like wasted time when you're excited to start gardening, but it's the most important investment you'll make.

Here's what you're tracking:

Sun patterns throughout the day. Walk out to your potential garden space at 8am, noon, 4pm, and 6pm every day for a week. Note which areas get direct sun, which get filtered light through trees or buildings, and which stay shaded. Take photos if it helps you remember.

Most vegetables need at least 6 hours of direct sun, but plenty of crops thrive with less. Lettuce, spinach, kale, and most herbs do fine with 3-4 hours. Understanding your light conditions prevents the heartbreak of watching sun-loving tomatoes struggle in a shaded corner.

Wind patterns and intensity. This is especially critical for balconies and patios. Strong winds dry out containers faster, can damage plants, and make tall structures unstable. But gentle air circulation is actually beneficial—it prevents fungal diseases and strengthens plant stems.

Note which areas are protected and which get blasted. That windy corner might be terrible for delicate lettuce but perfect for sturdy herbs like rosemary and thyme.

Water access and drainage. Where's your nearest water source? How far will you be carrying watering cans or dragging hoses? Is there a floor drain, or will water from containers just sit on the surface?

I learned this lesson at a Denver apartment where the nearest water was through the kitchen and down a hallway. Watering became such a chore that I started neglecting plants. Now I factor water access into every garden design.

Temperature extremes and microclimates. That corner where snow lingers in winter might stay cooler in summer too. The spot next to a brick wall might be several degrees warmer than the rest of your space. These microclimates become tools once you learn to recognize them.

Container Gardening Fundamentals: What's Different

If you've done any traditional gardening, you need to unlearn some assumptions. Container gardening isn't just "regular gardening in pots"—it's a different system with different rules.

Soil: Your Foundation

This is where most beginners go wrong. Garden soil—the stuff you'd dig up from a yard—is terrible in containers. It's too heavy, doesn't drain well, and compacts into a brick-like mass that roots can't penetrate.

You need potting mix, which is specifically formulated for containers. It's lighter, drains better, and stays fluffy even when wet. Yes, it costs more than garden soil, but it's not optional.

A good potting mix should feel light and springy when you squeeze a handful. It should contain ingredients like peat moss or coconut coir (for moisture retention), perlite or vermiculite (for drainage), and composted bark (for structure). Avoid mixes that feel heavy or contain a lot of sand.

For a basic setup, budget about $3-5 per cubic foot of potting mix. A 7-gallon container needs roughly 1 cubic foot of soil. This adds up quickly, but you can reuse and amend the soil year after year, so think of it as an investment.

Water: More Art Than Science

Container plants need water more frequently than ground plants, but they also need good drainage. This seems contradictory until you understand what's happening.

In containers, roots are confined to a small volume of soil that heats up and dries out faster than ground soil. But if water can't drain out the bottom, roots sit in soggy conditions and rot. The solution is frequent watering with excellent drainage.

Every container needs drainage holes. If you're using decorative pots without holes, either drill some or use them as cachepots with a plain plastic pot inside. The "layer of gravel in the bottom" trick doesn't work—it actually makes drainage worse by creating a perched water table.

Watering frequency depends on container size, plant type, weather, and soil mix. Small containers dry out faster than large ones. Vegetables need more water than herbs. Hot, windy days increase water needs dramatically.

The finger test is your best friend: stick your finger 1-2 inches into the soil. If it's dry, water deeply until water runs out the drainage holes. If it's still moist, wait.

Light: Quality Over Quantity

Most gardening advice talks about "full sun" (6+ hours) versus "partial shade" (3-6 hours) versus "shade" (less than 3 hours). But in container gardening, the quality of light matters as much as quantity.

Morning sun is gentler and less likely to stress plants than harsh afternoon sun. Filtered light through a tree canopy can be more valuable than direct sun reflected off concrete. Light that moves across your space throughout the day is better than static light in one spot.

This is why that north-facing balcony I thought was hopeless actually grew amazing lettuce and herbs. It got bright, indirect light for most of the day without the scorching afternoon sun that would have made those crops bolt.

If you're working with limited light, focus on crops that tolerate shade: leafy greens, herbs, and some root vegetables. Save the sun-lovers like tomatoes and peppers for your brightest spots.

The Vehicle Test: Planning for Portability

Here's the reality check that separates successful renter gardens from expensive mistakes: if you can't fit your garden in your vehicle, you don't have a portable garden. You have a temporary installation that you'll abandon when you move.

Before you buy containers, measure your car's cargo space. Length, width, height, and any awkward angles or wheel wells that limit how you can pack. Take photos and keep the measurements on your phone.

My Subaru Outback can fit 30 fabric grow bags (7-gallon size) plus tools and supplies. I know this because I've done it multiple times. This number shapes every garden decision I make. If I want more containers, I need to plan for multiple trips or borrow a truck.

The vehicle test isn't just about container quantity—it's about container type. Those beautiful ceramic pots might look great on Pinterest, but they're heavy, fragile, and awkward to pack. Fabric grow bags fold flat when empty and stack efficiently when full. Lightweight plastic containers nest inside each other.

Think modular. Instead of one large planter, use several smaller ones that can be rearranged and packed efficiently. Instead of a permanent trellis system, use stakes and ties that disassemble quickly.

Assessing Your Resources: Time, Money, and Energy

Be honest about what you can realistically maintain. A garden that requires daily attention will fail if you travel frequently for work. An expensive setup will create financial pressure that takes the joy out of gardening.

Time: How much time can you realistically spend on garden maintenance each week? Watering takes 10-15 minutes daily during peak season. Harvesting, pruning, and general maintenance add another hour or two per week. Factor in setup time at the beginning and moving time when you relocate.

Money: Container gardening has higher upfront costs than ground gardening because you're buying containers and soil. Budget $20-30 per container for the first year (container, soil, plants, basic supplies). After that, annual costs drop significantly as you reuse containers and amend soil.

Energy: Physical and emotional energy both matter. Carrying watering cans up three flights of stairs gets old fast. Moving a garden every two years requires emotional resilience as well as physical effort.

Start smaller than you think you want. It's easier to expand a successful small garden than to rescue an overwhelming large one.

Making Peace with Imperfection

Your rental space will have limitations. The light won't be perfect. The layout won't match your Pinterest dreams. Your landlord might say no to your first proposal.

This isn't failure—it's the creative constraint that makes renter gardening interesting. Some of my most productive and beautiful gardens have been in spaces that seemed hopeless at first glance.

That north-facing Portland balcony taught me everything about shade gardening. The tiny Denver patio forced me to master vertical growing. The strict HOA landlord in the townhouse made me expert at attractive, contained designs.

Every limitation is also an opportunity to develop skills that most gardeners never need. When you can grow food in challenging spaces, you can grow food anywhere.

Your Space Assessment Action Plan

Before moving to the next chapter, complete this assessment of your rental space:

- Categorize your space: Apartment balcony/patio, townhouse patio, or house with yard access?

- Track sun patterns: Spend one week noting light conditions at different times of day.

- Measure your space: Length, width, and any height restrictions. Note weight limitations if applicable.

- Assess water access: Where's the nearest water source? Is there drainage?

- Apply the vehicle test: Measure your car's cargo space and calculate how many containers you can realistically transport.

- Evaluate your resources: Be honest about time, money, and energy you can commit.

- Identify microclimates: Note areas that are windier, warmer, cooler, or more protected than others.

This assessment becomes the foundation for every decision you'll make about containers, crops, and garden design. It's the difference between working with your space and fighting against it.

Remember: there's no such thing as a perfect rental garden space. There are only spaces you understand well enough to work with creatively. Your job isn't to find the ideal conditions—it's to make the most of the conditions you have.

In the next chapter, we'll take this assessment and turn it into a portable garden design that maximizes your space while staying true to the mobility that defines renter life. But first, you need to know what you're working with.

Take the time to really observe your space. The week you spend watching sun patterns and measuring corners will save you months of frustration and hundreds of dollars in mistakes. Your future gardening self will thank you.

Chapter 3: Designing Your Portable Garden: Systems That Move With You

2,902 words

I was standing in my driveway in Portland, staring at the beautiful cedar planters I'd built for my townhouse patio. They were gorgeous—perfectly sized for the space, weathered to a lovely grey, and filled with thriving tomato plants heavy with fruit. There was just one problem: I was moving to Denver in three days, and these planters weighed about 200 pounds each when full of soil.

That moment taught me the most expensive lesson of my gardening career: beautiful doesn't matter if you can't take it with you.

I ended up leaving those planters behind, along with the $400 I'd invested in building them and the soil that filled them. The new tenants got a lovely garden setup, and I got a harsh reminder that portable means portable—not just theoretically moveable.

This chapter is about designing garden systems that actually move with you, not just gardens that look good in your current space. After eight moves and countless mistakes, I've learned that true portability isn't an afterthought—it's the foundation that every other decision builds on.

The Portability Mindset

Before we dive into specific systems, you need to understand what genuine portability means. It's not enough for something to be technically moveable. If it requires three people, special equipment, or a moving truck to relocate, it's not portable for most renters.

Real portability means you can pack up your entire garden system in a few hours, fit it in your personal vehicle, and set it up again at your new place without professional help. This constraint might seem limiting, but it actually forces you to become a better designer.

When every container has to justify its weight and space in your car, you start thinking differently. You choose systems that serve multiple functions. You standardise sizes so things stack and nest efficiently. You prioritise durability because replacing gear every move gets expensive fast.

This mindset shift—from "what looks good" to "what works everywhere"—is what separates successful mobile gardeners from people who restart from scratch at every rental.

The Three Pillars of Portable Garden Design

Pillar One: Lightweight and Durable Materials

The material your containers are made from determines everything about their portability. I've tested just about everything over the years, and there are clear winners and losers.

Fabric grow bags are my absolute workhorse containers. They're made from breathable fabric that prevents root rot, they're incredibly lightweight when empty, and they fold completely flat for storage or moving. A 7-gallon fabric bag weighs about 8 ounces empty but can hold the same amount of soil as a ceramic pot that weighs 15 pounds before you add any growing medium.

The fabric also provides better root health than plastic or ceramic. Roots that hit the fabric walls get "air pruned" instead of circling around the container, which creates a healthier root system and better plant growth. I've used the same fabric bags through multiple moves and they're still going strong after five years.

Food-grade plastic containers are my second choice. They're lightweight, durable, and you can often find them free or cheap from restaurants and food service companies. Five-gallon buckets with lids are particularly useful because you can store tools or soil amendments inside them during moves.

The key with plastic is choosing containers designed for outdoor use. Indoor storage bins might seem like a bargain, but they'll become brittle and crack after a season in the sun. Look for containers marked with UV resistance or designed for nursery use.

What to avoid: Ceramic pots, concrete planters, and wooden containers are beautiful but impractical for mobile gardening. Even "lightweight" ceramic pots become back-breaking when filled with wet soil. I learned this lesson with a set of gorgeous glazed pots that I could barely lift when planted, let alone move efficiently.

Terra cotta deserves special mention because it's so common. While it's lighter than ceramic, it's also fragile and porous. Terra cotta pots dry out faster than other materials, requiring more frequent watering, and they crack easily during moves. Save yourself the heartbreak and choose something more practical.

Pillar Two: Modular and Standardised Systems

The second pillar is designing your garden as a collection of interchangeable modules rather than a custom installation. This means choosing containers in standard sizes that stack, nest, or pack efficiently together.

I use primarily 5-gallon and 7-gallon fabric grow bags because they hit the sweet spot between growing capacity and portability. A 7-gallon bag can grow a full-size tomato plant but still weighs less than 50 pounds when planted. More importantly, I can fit exactly 30 of them in my Subaru when moving.

This standardisation extends beyond just containers. I use the same type of plant stakes (bamboo canes that nest together), the same style of plant ties (velcro strips that can be reused), and the same basic trellis system (tension-mounted poles that require no tools to assemble or disassemble).

When everything in your garden uses the same basic components, packing becomes routine instead of a puzzle. You know exactly how much space you need, how much weight you're dealing with, and how long setup will take at your new place.

The modular approach also makes expansion easier. Instead of planning one large garden bed, you're building a collection of portable growing modules. Want more space? Add more containers. Need to downsize? Remove a few modules and store them empty. This flexibility is invaluable when you're not sure what your next rental will offer.

Pillar Three: Vehicle-Centric Planning

This is where most people's portable garden dreams crash into reality. You can have the most lightweight, modular system in the world, but if it doesn't fit in your vehicle, you don't have a portable garden.

Before you buy a single container, measure your car's cargo space. Length, width, height, and any awkward angles or intrusions like wheel wells. Take photos and keep these measurements on your phone because you'll reference them constantly.

My Subaru Outback has become the template for all my garden planning. With the rear seats folded down, I have roughly 70 cubic feet of cargo space. Through trial and error (mostly error), I've learned that this translates to 30 fabric grow bags, plus tools, stakes, and other supplies.

This number—30 containers—shapes every decision I make. If I want more growing space, I need to plan for multiple trips or borrow a larger vehicle. If I'm considering a different container type, I calculate how many will fit compared to my standard bags.

The vehicle test isn't just about quantity—it's about shape and weight distribution too. Round pots waste space compared to square or rectangular containers. Tall, narrow containers might not fit under your car's rear hatch. Heavy containers need to be positioned over the axles, not hanging off the back bumper.

Some practical vehicle considerations I've learned:

- Fabric bags pack most efficiently when they're about 80% full of soil—full enough to hold their shape but not so full they can't compress slightly - Wet soil is significantly heavier than dry soil, so plan your moving day around weather if possible - Plants themselves take up more space than you'd expect—a tomato plant with a cage can easily double the height requirement - You'll need space for tools, extra soil, stakes, and all the small items that make a garden function

Three Proven Portable Systems

After testing dozens of approaches across eight rentals, I've settled on three core systems that work reliably for different situations and space constraints.

System One: The Fabric Bag Foundation

This is my go-to system for most situations. It's based on fabric grow bags in standardised sizes, primarily 5-gallon and 7-gallon containers. The beauty of this system is its simplicity and flexibility.

For vegetables: 7-gallon bags work for tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, and other full-size plants. 5-gallon bags are perfect for herbs, lettuce, and smaller vegetables like bush beans.

For arrangement: I group containers on plant stands or wooden pallets to create different levels and improve drainage. This also makes it easier to move the entire setup—you can slide a pallet with several containers rather than moving each bag individually.

For support: Bamboo stakes or collapsible tomato cages provide plant support without permanent installation. Everything disassembles quickly and packs flat.

The fabric bag system works in any rental situation—apartment balconies, house patios, or yard spaces. It's weather-resistant, provides excellent drainage, and the containers actually improve with age as the fabric becomes more flexible.

System Two: Vertical Gutter Gardens

When floor space is limited, going vertical multiplies your growing capacity. My vertical gutter system uses standard vinyl rain gutters from the hardware store, mounted on removable brackets or hung with heavy-duty hooks.

The components: 10-foot vinyl gutters ($8 each), end caps ($2 per gutter), mounting brackets or heavy-duty S-hooks, and drill bits for drainage holes. Total investment is usually under $50 for a system that can produce salads for months.

Installation: The key is making everything removable. I use tension-mounted poles between floor and ceiling (for covered patios) or heavy-duty hooks that hang from existing structures. No permanent mounting means no landlord concerns.

What grows well: Lettuce, spinach, herbs, strawberries, and other shallow-rooted crops thrive in gutters. The long, narrow shape is perfect for succession planting—you can harvest from one end while new seedlings establish at the other end.

Portability: When it's time to move, you simply unhook the gutters, dump the soil (which can be reused), and pack the lightweight components. The entire system fits in a couple of boxes.

This system has moved with me to three different rentals and produces consistently. It's particularly valuable for renters with shaded spaces, since many gutter-appropriate crops tolerate partial shade.

System Three: Mobile Raised Bed

For renters with patio or yard access who want the benefits of a raised bed without the permanence, a mobile raised bed offers the best of both worlds.

The design: A 3x3 or 4x2 foot raised bed (12 inches deep) built on a platform with heavy-duty locking caster wheels. The bed itself is constructed with basic lumber and corner brackets—no complex joinery required.

The mobility: Locking casters rated for at least 200 pounds each allow you to move the bed to chase sun, clear space for other activities, or roll it directly into a moving truck. The mobility also helps with landlord negotiations since you can demonstrate that it's truly temporary.

What it's good for: Crops that benefit from deeper soil and more root space—tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, squash, and root vegetables. The larger soil volume is more forgiving than individual containers and holds moisture better.

The reality check: This system requires the biggest investment ($150-200) and only works if you have relatively flat, hard surfaces. It's also the heaviest system when planted, so you need to be realistic about your ability to move it when full of wet soil.

I've used mobile raised beds at two rentals with great success, but I've also learned they're not for everyone. If you're not comfortable with basic carpentry or don't have appropriate space, stick with the fabric bag system.

Design Principles That Apply to Every System

Start Small and Expand Gradually

Every successful mobile garden I've seen started smaller than the gardener initially wanted. This isn't a limitation—it's a strategy. Starting with 6-8 containers lets you learn your space, understand your maintenance capacity, and refine your systems before scaling up.

I see new gardeners get excited and immediately plan for 20 or 30 containers. Then they get overwhelmed with watering, maintenance, and the sheer logistics of managing that many plants. They burn out and give up, convinced that container gardening doesn't work.

Start with enough containers to grow herbs and salads—maybe 6-8 containers total. Master those crops, understand how much time and effort they require, then expand based on your actual experience rather than your initial enthusiasm.

Design for Your Weakest Link

Your garden system is only as portable as its least portable component. That beautiful wooden trellis might work great until moving day when you realise it doesn't disassemble. The perfect ceramic pot becomes a liability when you can't lift it safely.

Before adding any component to your garden, ask yourself: Can I move this alone? Does it pack efficiently? Will it survive multiple moves? If the answer to any of these questions is no, find an alternative.

This principle extends to plants too. That slow-growing fruit tree might seem like a great investment, but if you move before it produces, you've wasted time and money. Focus on crops that give you returns quickly and can be easily replaced if necessary.

Plan for the Unexpected

Rental life is unpredictable. Leases don't get renewed. Job opportunities arise in other cities. Landlords sell properties. Your garden design needs to accommodate these realities.

This means avoiding anything that requires a full growing season to justify its cost. It means choosing containers and systems that can be packed quickly if you need to move on short notice. It means focusing on crops that produce continuously rather than all at once.

I learned this lesson when I had to move in the middle of tomato season. The plants that were just starting to fruit had to be harvested green or left behind. Now I time my plantings so that most crops will have produced significantly before my lease renewal date.

The Portability Checklist

Before investing in any garden component, run it through this checklist:

Weight Test: Can I lift this when full/planted? Can I carry it a reasonable distance?

Vehicle Test: Does this fit in my car? How many can I transport at once?

Assembly Test: Can I set this up and take it down without special tools or help?

Durability Test: Will this survive multiple moves and seasons of outdoor use?

Value Test: If I have to abandon this, will I regret the investment?

Components that pass all five tests become part of your portable garden toolkit. Everything else, no matter how attractive or clever, stays at the garden centre.

Common Portability Mistakes

After helping thousands of renters design portable gardens, I see the same mistakes repeatedly:

Choosing containers that are too small: Tiny pots look cute and seem portable, but they dry out constantly and limit plant growth. The time you save moving small containers gets eaten up by daily watering and poor harvests.

Mixing too many container types: Using five different styles of pots might look interesting, but it makes packing a nightmare. Standardisation isn't boring—it's efficient.

Ignoring weight distribution: Loading all your heavy containers in the back of your car affects handling and might exceed weight limits. Distribute weight evenly and keep the heaviest items over the axles.

Forgetting about soil: Containers are just part of the equation. You also need to transport or replace soil, which is heavy and bulky. Plan for this in your vehicle calculations.

Underestimating setup time: Moving isn't just about transport—it's also about setup at your new place. Design systems that can be reassembled quickly so your plants don't suffer extended stress.

Making Portability Beautiful

The biggest objection I hear about portable garden design is that it looks too utilitarian. People want their gardens to be beautiful, not just functional. But portability and beauty aren't mutually exclusive—they just require different design thinking.

Grouping and arrangement can make even basic containers look intentional. Cluster containers in odd numbers, vary heights with plant stands, and use consistent colours or materials.

Plant selection matters more than container style. A thriving basil plant in a plain fabric bag looks better than a struggling plant in an expensive ceramic pot.

Temporary decorative elements can add beauty without compromising portability. Outdoor rugs, string lights, and small decorative objects can transform a utilitarian setup into an inviting space.

Seasonal flexibility lets you adapt your garden's appearance throughout the year. Swap out annual flowers, add seasonal decorations, or rearrange containers to keep things fresh.

Remember: the most beautiful garden is one that's thriving. A healthy, productive portable garden will always look better than an expensive setup that's struggling because it wasn't designed for your actual situation.

Your Portable Design Action Plan

Before moving to the next chapter, complete these design steps:

- Measure your vehicle's cargo space and calculate your container capacity

- Choose your primary system based on your space, budget, and skill level

- Start with 6-8 containers in standardised sizes

- Source your containers and basic supplies using the portability checklist

- Plan your first layout with moving in mind from day one

Remember: the goal isn't to create the perfect garden immediately. It's to build a system that works reliably, moves efficiently, and can evolve with your changing rental situations.

Your first portable garden will teach you lessons that inform your second, which will be better than your third. Each move becomes an opportunity to refine and improve rather than start over.

In the next chapter, we'll explore the most common mistakes renters make when starting their portable gardens—and how to avoid the expensive lessons I learned the hard way. But first, you need a design foundation that prioritises portability from day one.

That beautiful cedar planter I left behind in Portland taught me that gardens tied to places aren't really yours. But a well-designed portable system? That travels with you, improves with experience, and produces food wherever you call home.

That's the kind of garden worth building.